Many of us have experienced the magic effects of a well-designed space. Somewhere that flips a switch inside of you as soon as you set foot in the door. There's a rhythm in the air of these spaces that induce flow states, mood changes and creative output. Sitting down, you feel a powerful wave of calm and focus overcome you. Thoughts of avoidance, distraction and self-doubt fade into the background as you set to work on moving the mountains in front of you.

This is the power of context - the spaces we find ourselves in shape our capacity for doing. Harnessing this power means applying contextual leverage to our lives - small changes in the design of our environment that deliver outsized returns in how we act.

When it comes to mastering our behaviour, our output and our creativity, it is important to heed the words of writer Stephen Johnson:

"Our thought shapes the spaces we inhabit, and our spaces return the favour."

Broken Windows & The Power of Context

Our body is primed to perceive cues. Signals given off by the things around us are reflected back onto our thoughts and actions in ways that we aren't always aware of. Malcolm Gladwell in The Tipping Point aptly describes this as the power of context:

"we are more than just sensitive to changes in context. We're exquisitely sensitive to them."- Malcom Gladwell, The Tipping Point

In his book, Gladwell tells a great story about New York City crime in the 1990s. In the 80s, New York City crime ran rampant. In a single year, there were over 600,000 serious felonies and 2000 murders committed in the city and yet, by 1996, felonies were down 40% and homicide rates halved. Why was this?

Gladwell explains that on a broad scale crime levels in the US were decreasing over this period as the economy improved, the population aged and the crack trade declined but what made for such a significant drop in New York compared to the rest of the US was the implementation of the Broken Windows Theory.

Building on the work of Stanford psychologist Philip Zimbardo (famous for designing the 1971 Stanford Prison Experiment), George Kelling and James Wilson posited the Broken Windows Theory which linked crime with context:

"crime is the inevitable result of disorder. If a window is broken and left unrepaired, people walking by will conclude that no one cares and no one is in charge. Soon more windows will be broken, and the sense of anarchy will spread from the building to the street on which it faces, sending a signal that anything goes."

As one study in the Netherlands found: “One example of disorder, like graffiti or littering, can indeed encourage another, like stealing.”

David Gunn, as head of the New York Transit Authority, started a campaign to eliminate subway car graffiti which he saw as "symbolic of the collapse of the system." William Bratton, as New York City police commissioner, began cracking down on fare avoiding turnstile jumpers and behaviour like public drinking and street prostitution through the introduction of the “quality of life" initiative.

By the late 1990s, these policies built on the Broken Windows Theory had worked to drive down New York City crime rates, having a knock on effect far beyond the small infractions they were targeting. Both Gunn and Bratton’s unintuitive decision to focus on petty crime instead of seemingly more pressing issues worked to eliminate signs of disorder from the streets and subways and as result, triggered the tipping point of New York crime.

What this story and the Broken Window Theory tells us is that our internal decisions are subtly influenced by our external realities. If broken windows, graffiti and turnstile jumpers can shape the levels of crime in a city, then it is certainly not a stretch to suppose that where we decide to sit down, open up our laptop and get to work can measurably influence the quality of our output.

The question then is how can we be intentional in applying this power of context for our benefit?

Habits & Controlling Cues

Habits are the unconscious responses that are key to making desired changes in our lives. Good habits are the "compound interest of self-improvement" and make up the systems that steer us towards our goals. Mastering our habits is mastering our output. This is why the first aspect of contextual leverage is designing our environment to create good habits and eliminate bad ones.

In Atomic Habits, James Clear provides insights on how we form habits: the four step process of cue, craving, response and reward. Based on this, he shares how we can effectively build good habits and break bad ones through strategies distilled in the Four Laws of Behaviour Change, the first of which states:

"Make cues for good habits obvious and make cues for bad habits invisible."

We know from the Broken Windows Theory that the impetus for certain kinds of behaviour comes from the cues around us. To take control of our behaviour and habits, we must make take action to control the cues in our environment. Eliminate cues that work against you and create cues that work in your favour.

As Clear tells us in his discussion of law one:

"Environment is the invisible hand that shapes human behaviour"

Here are some examples of this advice put into practice:

- If you want to drink more water, keep a full water bottle on your desk that reminds you to drink every time you happen to glance at it

- If you want to build a daily journalling practice, keep your notebook and pen on your bedside table

- If you need to take your vitamins every morning, put the bottle next to your toothbrush

- If you want to play video games less, keep the console outside of your room or in a sealed drawer

- If you want to stop reaching for the cookie jar, take it off your kitchen counter and fill the newly liberated space with healthier alternatives

The most powerful and low effort example of this for me comes from managing my smartphone use. After hearing about a study which showed the 'brain draining' effects of just having a smartphone (whether on or off, face down or face up) on your table, I was prompted to make changes in how I worked.

Since then, whenever I prepare for focussed work, I place my phone somewhere out of reach and, more importantly, out of my field of view. By hiding my phone away in my bag or another room and actively controlling my environment, I (1) remove the stream of distracting notifications that threaten to pull me away from progress and (2) eliminate the possibility of seeing my phone and reaching for it when my mind begins to wander.

But what's even more powerful about this ritual is that the act of removing my phone from the environment has in itself become a positive cue that gives me focus and tells my brain it's time to work. This is an example of how cues become associated with good habits and others report the same positive effects: gaining sudden focus when putting in their earphones or feeling energised when changing into sports clothes.

Ultimately, it is our relationships with the objects in our environment and not the objects themselves which can influence how we act. Control over our environment allows us to form unrelated cues which trigger our desired behaviour.

Segmentation

Segmentation is another important tool in applying contextual leverage which involves splitting up our spaces based on how we plan to use them.

It is important that we allocate a place for focus, a place for play, a place for creativity and whatever other needs we may have. Through consistent action surrounded by the same environmental cues, this primes our brain to respond to each space in a consistent way, effectively allowing us to inspire action by shifting locations.

Premeditating on the purpose of different spaces allows us to influence our behaviours when we transition between them. It also avoids non-compatible areas of our lives mixing together and producing conflicting signals:

- Your bed should be a place to sleep, not to scroll through social media

- Your office shouldn't be a place to play video games

- Your living room should be a place to relax and not bring the stress of work

Even just segmenting different areas within the same room help us to establish clearly defined areas of work. Having a designated chair in the room for reading overtime will make just sitting in that chair become a cue for picking up and focussing on a good book.

"Think in terms of how you interact with the spaces around you. For one person, her couch is the place where she reads for an hour each night. For someone else, the couch is where he watches television and eats a bowl of ice cream after work. Different people can have different memories—and thus different habits—associated with the same place."- James Clear, Atomic Habits

Priming Your Senses and Emotions

Related to habits and cues, our senses influence our emotions which have a cascading effect on our behaviour. We can apply contextual leverage in the design of our working environments to take advantage of this and improve our creative output.

Applying the Pareto Principle to look for the 20% of changes that can provide 80% of the benefits, our focus should fall on these things: visual minimalism, lighting, sound and scents.

Visual Minimalism

As humans, sight is our most developed sense and shapes the way we think. Large portions of neural tissue in the brain are devoted to processing visual information. By limiting that stream of information, we can focus our bandwidth on what is essential for our desired action.

As our attention wanes, both our mind and eyes starts to wander away from our work. The objects around us can either provide us with a kick of motivation to get back on track or lead us down procrastinating rabbit holes.

Eliminate distractions and pair down what is in your workspace to only things that inspire. Remove the phone, the toys and the mess, organise those piles of papers, return tools to their proper place. Set aside time for reorganising and restoring order to your space.

For me, I dedicate every Sunday morning to my 'Sunday Reset' practice where I take care of the maintenance overhead in my life - cleaning and reordering both digital and physical spaces.

Another great habit you can build is to make sure that your space has been sufficiently reordered before transitioning from work to pure entertainment.

A clean space is like the blinkers race horses wear, restricting their vision to only what is in front of them. Applying constraints allow us to direct our limited attention towards what is important to us.

Lighting

We are becoming more aware of the effects of blue light on our health and wellbeing. But even more striking is recent research that points to the ability of blue light to promote brain activity, reaction times and attention. Lighting has also been shown to influence our mood and act as potential treatment for seasonal affective disorder, anxiety and premenstrual depression.

The biggest improvement to my space has been controllable lighting. Products like the Philips Hue line (or cheaper Amazon alternatives) offer a way to set light to match your current state or prompt a change towards a desired state.

The two Philips Hue Play bars behind my monitor are set to bright white light when I need energy, warm light when I'm reading, thinking or being creative and colourful lights for pure play. In my experience, this has given me more control over regulating my inner state and has stopped me from losing focus on multiple occasions.

As an alternative, consider choosing spaces with abundant natural lighting, such as coffee shops with open windows, for periods of focussed determination.

In controlling our lighting, we take advantage of the neural wiring that evolution gave us to influence our mental states.

Sound

We are all aware of how music can affect our moods. We perceive patterns of pitches, harmonies, rhythms and tempos in different regions of our brain, which all have an effect on the way we feel. Music has even been shown to reduce heart rate, blood pressure, stress and inflammation markers in surgery patients and have benefits for those suffering from depression, anxiety and sleep disorders.

Some suggestions to control the effects of sound on your mood include:

- Matching music tempo with the pace of your work

- Listening to music without lyrics or in another language to avoid distraction

- Playing ambient sounds or white noise if music distracts

- Playing music at a medium volume

- Using noise cancelling earphones to drown out the outside

Scents

I only have two things to say about scents:

- Buy a candle that you like and light it when you prepare to work

- A two-bird-one-stone solution is to brew coffee or tea when you're working for a caffeine and sensory boost

New Spaces, New Routines, New Ideas

The first 3 points came down to controlling the spaces we frequent most often and establishing routines around these spaces. That is because consistent exposure to cues leads us to consistent patterns of action.

But when applying contextual leverage, it is also important to consider how we expose ourselves to the new. Our mind responds fondly to new stimulus and we can harness that in controlling how we expose ourselves to new spaces.

A blank slate

Habits and practices are easier to build in new environments free of established cues. They are blank slates for our mind to establish new patterns of behaviour as opposed to familiar environments where we have to actively work to rewrite old bad habits and existing relationships.

Obviously, you can't buy a new house or renovate every time you find yourself falling into a bad habit but you can always reorder your space or introduce new things to reestablish the markers of your behaviour.

Think and list out the functions of a space and the consistent practices you want to build before you use it. For a new office this might include: getting right to work once you sit down and not checking your phone, cleaning your desk after everyday of work, getting up every 30 minutes to walk around or stretch etc.

Use the blank slate to write good practices.

New Stimulus

New spaces inspire new thinking. If you find yourself stuck on a decision, problem, or creative project it often helps to put yourself into a new space to escape the same cyclical patterns of thought.

Obama recently wrote about the process of decision making and how he approached the tough choices that naturally come with being president. This line really resonated with me:

"You also want to create space to think. Remember that dinner and haircut break I took during that marathon economic session? That mattered, too. That was part of making the decision. Even in situations where you have to act relatively quickly, as was frequently the case during the financial crisis, it helps to build in time to let your thoughts marinate."

As you see, hear and feel new things, your mind escapes its routine thoughts. Your exposure to new sensory information lights up new parts of the brain. It allows you to link information in previously unseen ways and approach old problems with new ideas. Just taking a break to walk to the cafe across the road has the added benefit of activating our diffuse mode thinking and helps avoid the Einstellung effect (repeatedly approaching a problem with the wrong solution).

To avoid going to the same Starbucks every time you leave the house, make it a habit to research and write down the next space that you want to go to before you leave your current workplace or develop a rotation system. This will keep things changing and avoid having new spaces become routine spaces.

Explore a new building, a new street or a new part of town and find a place to sit down. Your brain will reward you for stimulating it in new ways.

Make Your Goals Obvious

One last thing to remember is that it can be easy to get caught up in the doing and forget the why. When work gets hard and our determination and attention dries out, it can be hard to do things for our future selves and consider the long term benefits that come from short term sacrifices. One solution is to leverage our environment to keep our goals in mind.

If you want to remind yourself to feel inspired, write down your goals on a sticky note to paste on your computer screen. Better yet, you can hijack your brain's visual reliance and turn these goals into a graphic with images that remind you of your core values and pursuits. Put it up on your wall or make it your computer/phone wallpaper to remind yourself constantly of the why behind what you're doing or the how that you should be following. This has worked really well for me and helps me to remember the doctrines that I seek to follow in my work as well as the importance of what I'm doing.

Another effective change to my digital space has been reminding myself of my long-term goals by including them above my daily reflection page in Notion. I visit this page first thing in the morning and last thing before bed which ensures I wake up and go to sleep every night excited to get to work and take steps that will bring me closer to my goals.

Also remember that choosing good things to do is step one to doing good things and is essential to avoid falling victim to busy work and illusions of productivity. Constantly revisit the why's in front of you and question if what you're doing is the right thing.

Keep your goals, systems and beliefs in your mind and they will carry you down the path you want to go.

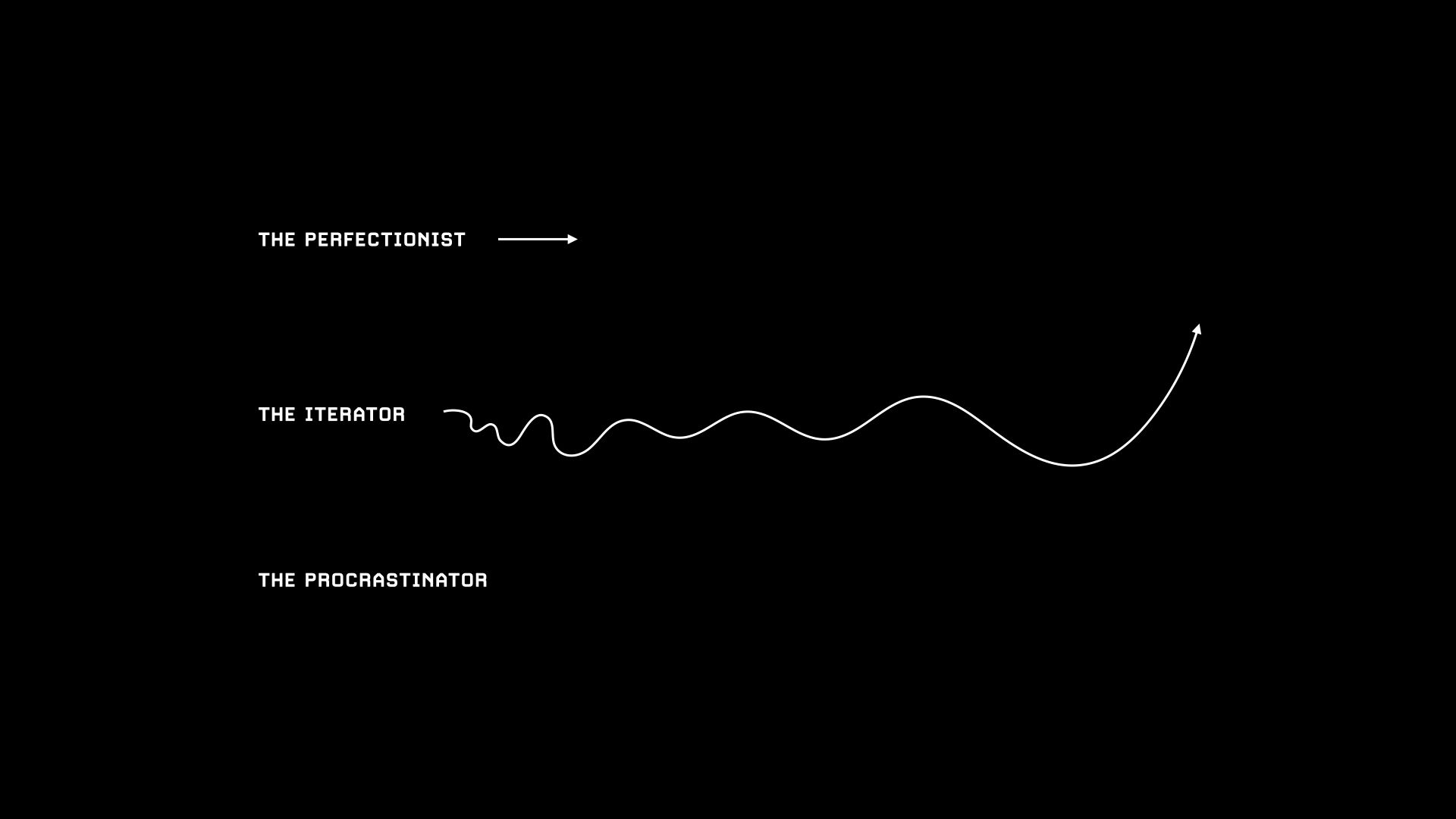

Perfect is the Enemy of Good

Voltaire famously wrote "Perfect is the enemy of good." Perfection is an unattainable ideal that we often find ourselves pouring time and efforts into at the expense of doing more meaningful work. The opportunity cost of perfectionism - working with good enough and putting time towards doing, creating and learning more- is too high for the marginal benefits we gain from it.

Gall's Law states that "all working complex systems come from simple systems that work" and this is important to keep in mind as we apply contextual leverage to our lives. Find the simple systems that work for you and iterate on them over time as you experience the feedback loop that drives progress.

Your systems will not be perfect. Instead, they should seek to be improving. Save the hours building perfection and spend them on doing the work you're trying to optimise for. Recognise when good enough is good enough.

Compounding Changes

We often think that what is holding us back from achieving our goals is a lack of motivation. We believe that all we need to do is push a little harder or want a bit more. But our minds are built to follow the Principle of Minimum Energy which tells us to avoid the hard stuff and seek out the easiest form of deriving pleasure. Willpower is a limited resource that cannot be depended on as the only source of making meaningful change in our lives.

Instead of actively fighting the resistance to act, we can passively reduce that resistance by controlling the sensory information that flows to our brain. Small positive changes to our spaces produce 1% improvements in the way we think and act that compound over the countless hours spent inhabiting them:

Intentional environment design reduces the mental friction towards our desired behaviour by creating/removing cues for our habits

Segmenting spaces avoids conflicting signals

Controlling our senses is controlling our emotions and thus our action

New spaces give a blank slate for new practices and promote new thought

Integrating goals, systems and beliefs into our environment reminds us of the how and why behind what we do

Contextual leverage offers us a way to work smarter not harder. It helps us reduce the friction that surrounds the behaviour where our best interests lie. It tells us that we can predispose ourselves for better thoughts through the intentional choices we make in designing our environment. It gives us the chance to make our spaces work for us.

This is the power of contextual leverage.